|

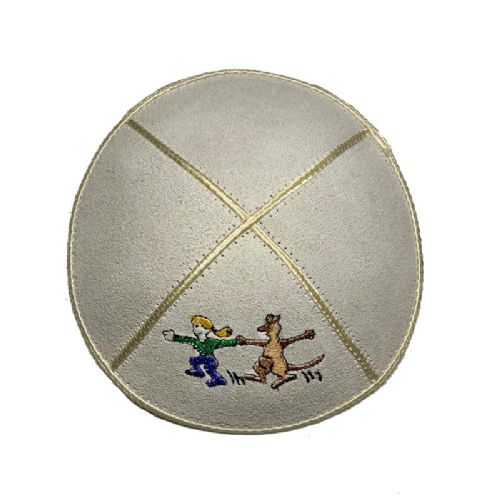

“That terrible noise, what is it?”, my friend asked me, looking at the Balaclava Junction while having a latte at Bonbons. “There must be something loose with the tram line”, he continued. “You can hear that noise every time a tram or car passes the Junction.”

“It’s not the tram line, it’s the heart of the tram line that’s loose.”

“What do you mean the heart?”

“The heart”, I answered, “is the centre piece of a tramline junction, or a train junction. They call this ‘DAS HERZ STUCK’.”

|

|

1943

“Eins – Zwei – Drei – Hoch” (One – Two – Three – Up), Herr Helmut’s our foreman) voice was strong and sharp. In one second twenty prisoners, mostly from France and Belgium, using iron pliers, lifted the fifteen-metre long rail, ten on each side of that heavy thing. The move had to be synchronised – “If only one” Helmut warned us again and again, “is out of time, the metal track will collapse and fall on your feet.”

Once up, on the second command, they moved the track towards the sleepers a metre or so away, and on the third command, they let it down gently to rest on the sleepers.

“It must be tough for them”, I turned around to David, my partner in the job of nailing the track to the sleepers.

‘Them’ were the WEST-JUDEN, the Jews from the West, mainly Holland, Belgium or France.

‘Us’ were the Polish Jews.

Not used to the tough work and climate condition, the West-Juden were generally weaker, less resistant to any diseases and went downhill faster than us Polish Jews.

“Wait, Gustav, for a few days, when we get to the CENTRE PIECE, the Junction point.”

“What do you mean?”

“You will see, you will see.”

I saw it a week or so later; that huge Centre Piece, an iron monstrosity with a square shape.

“This”, David pointed out, “will have to be lifted, moved and joined to the completed railway track.”

I looked at David. “Who can possibly shift this? There is no room to put the pliers, let alone to lift it.”

“So, Gustav, less prisoners would have to be used – no more than ten or twelve.”

Next day, on the morning appel, a group of stronger Polish Jews were selected. Some of them volunteered as they were promised some extra food – I can’t remember what it was, an extra soup card or a bit of bread.

They called him ‘Samson The Gibor’ (the strong). He didn’t actually have Samson’s figure. Short, well built with wide shoulders disproportionate to his height. With those shoulders he could lift a wagon and put it back on the rails, whenever one was derailed from that narrow rail track temporarily used while building the railway embankment.

Even the guards admired his strength, occasionally pushing a bit of bread into his hands, causing of course, Pavlov reflexes in our empty but envious stomachs.

Yozek (that was his name) was quite gentle and helpful, a rare characteristic among prisoners in those slave labour days.

“I knew he would be out” my friend Heniek tapped me on the shoulder when we saw Yozek stepping out and joining the line of volunteers that morning.

Half an hour or so later we were looking at the selected prisoners (you would call them today ‘the Dirty Dozen’) preparing the pliers and other tools needed for the job.

Then came the command. “EINS – ZWEI – DREI – HOCH”. Up it went, and it was slowly moved a few feet to the right. They were almost there!

“Oh God!” One of the prisoners tripped over something, let the pliers go, sending the load right on top of Josek’s left foot.

We all stood there in silence looking at Josek rolling over in pain. The centre piece which they called “das herz stuck” was ready to be attached to the railway track.

Later we saw Josek being taken away on a stretcher to be put on a waiting truck. Heniek in a trembling voice whispered into my ear in German “JA, DAS HERZ STUCK HAT KEIN HERZ NICHT” (Yes, that heart piece has no heart), as we all knew that Josek would be finished soon for good. Less injured or sick prisoners were so frequently selected for their final destination – Auschwitz.

“JA”, repeated Heniek again, “DAS HERZ STUCK HAD KEIN HERZ NICHT”

|

|

But das herz stuck HAD a heart, as we found out just after the liberation, that by some miracle or some help from above, Josek was in fact taken to a hospital in Breslau where they amputated his foot, and as a victim of an accident at work, was sent to another labour camp and somehow SURVIVED.

I have never come across him again.

|